HISTORY OF THE OLD SHEFFIELD PLATE

AND ITS COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT

This text is the result of a long and careful translation of the most important text ever written on the subject of “Old Sheffield Plate”:

“History of Old Sheffield Plate”

by the silversmith Thomas Bradbury, written and edited for the first time in 1912 through the memories of those who, like Bradbury, were still custodians of the secrets of this technique, the last generation to have learned this art as young people which later became obsolete. After years of oblivion, this fascinating story is now much discussed by operators in the sector and collectors. Often truths are mixed with legends and even more often a single cauldron of the world of silver plated is created, thus grouping together the noble Sheffield Plate made by electrolysis with its historically and materially more important ancestor made by die casting. The topic is so complex that not even Bradbury (quote) was fully aware of it, there are secrets and formulas that unfortunately disappeared together with their users or even missing documents that could shed light on some steps or tricks. While you read this treatise, always keep in mind one very important thing, namely that when the author says "today" he means in 1912, therefore even somewhat archaic terminologies or concepts now distant from us must obviously be read in the perspective of those last sumptuous years one step away from the nineteenth century and another away from the European decay brought about by the First World War of 1914.

Note that it mentions the existence of fakes already in the early 1900s.

Francesco Li Volsi

PREFACE

The aim of this work is to broaden the knowledge of the specimens of Old Sheffield Plate articles, which are now very valuable; trace the origin of the processes by which they were produced, provide some details about the producers and their factories, the localities, the workers and the methods adopted; this together with other details that could be interesting both for collectors and for those who trade in the products of a long-standing industry that has now fallen entirely into disuse. It is incorrect to say that the production of silver plated items on copper by the casting process, with silver edges and fine supports, and silver shields 1 , is a lost art. A large percentage of the molds from which these items were made in the past are still present in Sheffield, while the rolling mills still roll the sheets of molten silver and copper as in the past. There are also workers capable of undertaking the difficult processes of soldering on silver supports, rubbing-in 2 of silver shields and applying fine silver edges. The industry in its ancient form, however, seems destined never to be resurrected commercially again; we live in an age where people who buy plated items demand them in the cheaper varieties. The manufacturers and retailers come together to completely satisfy the public in this regard. The idea is gaining ground that modern plated items only need to last a few years - until owners tire of their styles, or the items are no longer used.

In writing on the subject of Old Sheffield Plate , it was felt essential to include some details regarding the production of close-plated ware 3 , silver cutlery, silverware and Britannia Metal . 4 The welding of layers of fine silver onto baser metals – a method long termed “ close plating ” – has such an ancient origin that it is lost in the mists of time.

The production of silver and silver-plated items began in the cutlery sector. Later, cheaper material than Sheffield plate , and more practical than pewter, was required. “ Britannia metal ” then developed. In Sheffield the main manufacturers, in the past as today, produced cutlery and articles, both in silver and plated; although the production of Britannia metal was not despicable overall in recent times, if a company had sufficiently large buildings to guarantee the introduction of further production activities.

In the discussion of the previous topics, the main aim in view has been the most correct possible representation of the production process by means of illustrations, with reproductions of specimens, manufacturers' names and brands found both on the Old Sheffield and on the close-plated articles . The names in the lists of Sheffield makers who registered a plater's mark at the Assay Office in Sheffield embrace virtually the entirety of the silversmiths of the time. Consequently, it was deemed necessary to provide a chronological representation, as accurate and orderly as possible, of the makers' hallmarks, as well as the authentic date letters, crown shapes and styles, and lions found on ancient silverware.

The hope is that such matters will now be stated on clearly defined lines, so as to afford every possible aid to collectors desirous of inquiring into the origin of their specimens.

The Author's task has been greatly facilitated by the publication of the official registers of all silver and pottery hallmarks, entered in the books of the Assay Office at Sheffield, to whose custodians he wishes to acknowledge his debt.

Even those who have lived in Sheffield all their lives have great difficulty in discovering credible information about the conditions under which the industry was founded and developed; However, diligent research among the dusty archives of his own and other companies has allowed the Author to recover many forgotten facts, which have shed new light on these conditions. At the same time he has endeavored, with what success it is up to the reader to judge, to provide human interest to the narrative by including all that is known of the personality and character of the characters to whom the Sheffield Plate owes its origin and excellence.

The quantity of Old Sheffield Plate produced abroad that can be found in this country today, or found abroad but produced in England, required the writing of a separate article on the subject. The hope is that the marks reproduced, and the details provided in Part VII of this work, will help shed light on a subject which for a long time in the past rather baffled collectors.

The author trusts that the observations in the chapter: "Known places of production of Old Sheffield Plate ", will in turn help to resolve the age-old question of where plated ware was first produced.

On the subject of Britannia metal - an industry that has endured for 140 years now -, except for the few lines mentioned here, nothing, as far as the author knows, has yet been published.

I must thank with utmost gratitude for the invaluable help provided with the historical parts of the book Mr. Robert Eadon Leader, Graduate in Literature, descendant of one of the first and most accomplished blacksmiths and platemakers connected with our city, and who inherited the enthusiasm for the hometown, its trades, its personalities and the ancient history for which all true Sheffield natives are so proud of themselves. Mr. Leader's collaboration was particularly valuable because of his familiarity with our early documents, topographic and personal, and because he dedicated himself to preserving, before it was too late, details relating to our ancestors, their trades, customs and interests, together with much else which, in the changes brought about by the rapid development of the city, the introduction of advanced manufacturing methods and the colossal growth of the great steel factories, might soon have been lost into oblivion.

To Messrs. M. S. D. Westropp of Dublin, Clement H. Casley of Ipswich, Arthur Westwood of Harborne, near Birmingham, and B. B. Harrison of Sevenoaks, I must extend sincere thanks for their untiring assistance in recording and researching particulars concerning unusual specimens and other matters of 'interest; to Mr. W. P. Belk of Sheffield, for many suggestions of arrangement which have proved of inestimable use; and to Mr. GR Travis of Sheffield, for assisting me on the subject of the Old Sheffield Plate in France. From Mr. Pawson of Sheffield, I received valuable assistance in discovering local data and interesting material. Great assistance was given to me by Mr. A. Nicholson, of the Assumption Office in Sheffield. His grandfather has been ably described by one who can scarcely remember him as the last of the gentlemen Old Sheffield Plate makers.

I am also obliged to my brothers and Miss Bradury, the staff of T. Bradbury and Sons, especially Mr. G. H. Cottam, for bringing together the specimens of moulds, tools, etc., here illustrated; to Mr. G. Kinman for guiding me in technical matters; of Mr. Hunt for gathering information from old ledgers and manuscripts, and for his assistance in registering trade marks; of Messrs. T. Bradley and S. W. Turner.

By Maj. Carrington of Bideford, and the late Mr. Wm. A. Carrington of Bakewell, for assisting me in researching the family tree; of the late Mr. W. A. Ellis and Mr. P. M. Ellis of Birmingham, in connection with the practical aspects of fusion plating; also Messrs. Walter Willson of Richmond, J. H. Ellett Lake of Exeter, and F. Lyne of Bristol, whose careful recordings of the marks on the various pieces passed through his hands were most valuable to me, and who also sent me unusual specimens to examine; from Mr JB Mitchell-Withers of Sheffield, for providing information relating to his ancestor, Mr T. Boulsover; I also owe full acknowledgments of gratitude to Mr. W. Sissons for his valuable assistance in compiling documents relating to the early history of his firm and other matters connected with the subject of the Old Sheffield Plate.

For assistance in collaborating and loans of china for illustrations, I am indebted to Countess Sackville, Earl Fitzwilliam, Sir T. Freake, Baronet, Mr. Samuel Roberts, MP, Col. H. C. Surtees, the Mr JG Nairne of the Bank of England; by Mr. Walter Prideaux of Goldsmiths' Hall; the late Rev. J. Matthews of Broxbourne, and the Rev. F. L. Shaw, Vicar of Eyam; of the Keepers of the Assay Office at Sheffield, of the Cutlers' Guild, of Mr. L. T. O'Shea of the University; by Mr. ACC Jahn of the School of Art; by Mr. Bernard Watson, Graduate in Literature, Tasting Expert; by Mr JC Bennett of the Sheffield Smelting Company; of Col. Hughes, Companion of the Order of Bath, of Messrs. D. Vickers, Justice of the Peace, Arnold T. Watson, James Dixon, Justice of the Peace, Lennox Dixon, T. Bowker, AL Billot, TR Ellin, RT Wilson, W. Thorpe Haddock, AJ Hobson, Justice of the Peace, and Miss Hobson, of Messrs. B. Hoole, Herbert Hutton, Sidney Nowill, A. C. Ridge, Leslie Roberts, John Rodgers, H. B. Sandford, T. A. Scott, Henry Steel, W. O. Stratford, W. Walker, Cecil Wilson, all of Sheffield; by Mr WL Spiers of Sir John Soane's Museum; of Mr. L. Crichton., of Dr. W. Jobson Horne, of Messrs. George Lambert, A. M. Parsons, W. H. Rickatson, Frank C. Wheeler, G. N. Withers, Waldeck, all of London; of Messrs. Hiatt Baker of Almondsbury, near Gloucester; H. Hamilton of Belfast; by Dr J. Torrey Junior of Blundellsands; of Messrs. Joseph Spiridion of Cardiff; S. Barnett of Chester; HS Benzie of Cowes; of the Artistic and Industrial Section of the Irish National Museum; of Messrs. Hamilton Blake and EJ Inches of Edinburgh; former Glasgow City Councilor Sorley; of Messrs. Francis Mallett of Bath; G. H. Clapham of Manchester; F. A. Hawley of Hampstead; of Messrs. J. and H. Barraclough of Leeds; of Messrs. J. W. Usher of Lincoln; Alfred Bethell of Newton Kyme, near Tadcaster; J. Taylor of Northfield, near Birmingham; Alfred T. Johnstone of Rednal, and A. F. de Navarro of Broadway, Worcestershire; of Messrs. WT Freemantle of Barbot Hall, Rotherham; J. Tearoe, Justice of the Peace of Sanderstead; E. Plimmer of Shrewsbury; by Dr. A. M. Roberts of Southport; by Mr CA Head of Hartburn Hall, near Stockton-on-Tees; by Mr. Norman Haggie of Sunderland; by Dr. George Porter of Surbiton; of Messrs. H S Hare of Taunton; F. Ross of Winchester; WT Sears of Normanhurst, near Northhampton; Ernest Hill of Woking; Percy WL Adams of Wolstanton, Staffordshire; WJ Fieldhouse of Wooten Waven, and TP Barker of Four Oaks, Warwickshire; of Messrs. W. Birmingham Base; Felix Alfermann from Berlin; Henri Boulhet, Pinton, and Christofle of Paris; by Mr. Holbrook of New York.

Among members of the trade, my thanks for the kind grant of specimens go to Birch & Gaydon, Chapple & Mantell, Dobson & Son, Elkington & Co., Heming & Co., Holmes & Maplesden, Spink & Son Ltd., M . & S. Lyon, Mappin & Webb, F. B. Thomas & Co., Vander & Hedges, and Lambert, all London firms; to W. Dickinson and E. J. Vokes of Bath; SD Neill of Belfast; to D. & M. Davis, and to I. S. Greenbergh of Birmingham; to JH George, JH Mogg and FS Smith of Bristol; to T. Worthington, of Burton-on-Trent; to H. Winston of Cardiff; to A. Jack & Co., Martin & Co., and to A. Paget of Cheltenham; to Butt & Co. Ltd. and Lowe & Sons of Chester; to HC Galton of Christchurch; to HE Norris of Cirencester; to E. Johnson, JE Ledbetter, L. Wine and B. Wine of Dublin; at Wilson & Sharp in Edinburgh; to Bruford & Son, and to JE Lake & Son of Exeter; to R. & W. Sorley of Glasgow; to C. Basker & Son of Grantham; to Oswin & Co. of Hereford; to B. Mallinson & Son of Huddersfield; at Green & Hatfield in Ipswich; to S. Leighton of Lancaster; to Curtis & Horspool, and to William Withers of Leicester; to EE Dunthorne, Robert Jones & Sons, and RH Reed & Son of Liverpool; to L. Hall of Louth; to Sidney Blackford of Lynton; to ET Biggs of Maidenhead; to M. Beaver, D. F. Davis, and John Hall & Co. of Manchester; to H. T. Simmonds of Monmouth; at Ford & Son of Newark; to C. Ince of Newport; to Robinson & Co. of Northampton; to George Wood of Nottingham; to F. Cambray of Oxford; to E. Emanuel of Portsea; at Page, Keen & Page of Plymouth; to J. Cockburn and J. H. Harvis of Richmond; to R. Smith & Son of Scarborough.

FREDK. BRADBURY

SHEFFIELD,

OCTOBER 1912

THE HISTORY OF THE OLD SHEFFIELD PLATE

INTRODUCTION

Old Sheffield Plate is the term used to describe flat-ware [7] or hollow-ware [8] items, for tableware or for domestic use, made of silver-coated copper by melting; the production period dates from around 1743 and lasted approximately 100 years; it was then gradually supplanted by electrolytically silvered objects. In Sheffield plated ware, silver is spread over copper and the metals are joined by melting, hardened and strengthened by pressure between rollers. Unfortunately, as a rule, the knowledge of the average collector does not extend beyond the knowledge that Old Sheffield Plate consists of silvered copper, and they are sometimes tempted to buy electrolytically silvered-on-copper items when they see copper exposed in plain sight. Such items are not infrequently described as “ Real Sheffield ” 7 and “ Sheffield Plate ”, omitting the word “ Old ”. Our city is not, as has often been imagined, an Eldorado in which to find magnificent surplus examples of ancient plated wares, despite the fact that almost all pottery was produced there in times gone by, a period which today is familiarly described as " Old Sheffield ". There is a time-honored saying in the city - not without elements of truth - that good cutlery can be purchased almost anywhere except Sheffield, and both the cutler and the platemaker sought markets for their wares beyond outside the city limits. But undoubtedly there is still a large quantity of Old Sheffield Plate in Sheffield, mostly in private hands, and carefully preserved by the descendants of those who originally made it for their own use.

At Sheffield Parish Church there will be an exceptionally large Old Sheffield smooth plate or chopping board, used regularly to carry water to the source at baptisms. It is finely preserved and must have been used for a considerable number of years. It bears the mark of T. & J. Creswick. The church also contains - among other earlier specimens - some patens and jugs, the latter of a very large size, two of which were produced during the reign of Queen Anne, and in an excellent state of preservation. The pottery is well worthy of inspection by those interested in ancient silver.

At the Royal Infirmary of Sheffield there is a common communion service in Sheffield Plate honored by Thomas Law & Co. in 1800, including a paten, a chalice and a jug, bearing this mark (the flattened vase).

That Sheffield is a very old place from an industrial point of view is confirmed by a reference in Chaucer's "Reves' Tale", where the factor is described as follows:

“A thwytel 8 from Sheffield carries him in the barrel,

his face was round and his nose was snub."

There is a story of Edward III's hunting visit to Sheffield, so six centuries ago the city was not unknown to the court. The population of Sheffield in 1615 amounted to 2,207, of whom 1,222 were servants and children, and 725 "all poor beggars". However, this would lead one astray, except to remember that the information applies only to the city of Sheffield, not to the diocese, and that the wealthier inhabitants lived in the suburbs. A more useful comparison is made by taking the figures for the entire diocese. They indicate a population in 1736 of 14,105 inhabitants; in 1801, of 45,578; in 1841, of 110,891; in 1871, of 239,941. In 1905, when the borders had been extended, it was 440,414, and in 1911 it was 454,653.

Mary, Queen of Scots, spent approximately 14 years of her imprisonment in Sheffield, between 1571 and 1584, in the care of the Earl of Shrewsbury. At Sheffield Manor, now in complete ruin, there still exists a small detached building, carefully restored some years ago. One of his rooms, presumably reserved for the Queen's use, has beautiful interior decoration, including a finely executed Shrewsbury family coat of arms over the fireplace. It is claimed that this part of the Manor was built especially for her by the Count to prevent her escape.

An interesting portrait of Sheffield in the early Old Plate period is found in a letter from Horace Walpole to Mr. Montagu, dated 1 September 1760. The writer says:

“On my way to Lord Strafford I passed through Sheffield, which is one of the dirtiest cities in England, in the most charming condition, where there are 22,000 inhabitants who make knives and scissors. They pay £11,000 a week to London. A local man discovered the art of plating copper with silver. I bought a couple of candlesticks for two guineas which are very nice."

Among the city's ancient charitable institutions at least one was founded for the benefit of the local trade in silver and Sheffield Plate . In 1815, Mary Parsons, sister of John Parsons of J. Parsons & Co., extensive manufacturers of Old Sheffield Plate and silver, mainly candlesticks, "with affectionate regard to the memory of her brother", bequeathed a sum of £1,500 to credit for an investment, the proceeds of which would be distributed equally among 46 old and infirm Sheffield blacksmiths, in shares of £1 each, with a gift of £2 to the Vicar to recite an annual sermon on St John's Day. Increased by the sum of £175, raised in 1879 from the working manufacturers and blacksmiths of Sheffield, the endowment of this charitable institution now stands at £1,709, 17 shillings and 7 pence. Usually around 50 men received the annual fee of £1, and candidates were selected at an annual meeting of working blacksmiths. Benefits are limited to brasssmiths, pieceworkers and candlestick makers who have apprenticed in Sheffield and worked regularly in the trade. The beneficiaries usually go in procession to the church to listen to the sermon, after which the portion is distributed in the sacristy.

PART I

THE INVENTION

THE OLDEST PLATING METHODS

The methods by which the very first platers performed their work on larger articles used for decorative purposes are not very clear.

The dominant fact to always keep in mind is that, as in the case of today's electrolytically silvered items, the silver coating was applied after the items had been forged. The “French” method of plating, prior to the discovery of the fusion plating process, consisted of burnishing a thin sheet of silver struck at a low temperature onto the metal before oxidation took place, and although other sheets could be added, they could not never achieved a perfect union. A casing wrapped around the edges in baser metals had been tried, but it had a lamé-like appearance and was almost unusable.

That from ancient times cutlers used a process of plating baser metals with silver and gold for the ornamentation of knives is evident. As early as 1379, the cutlers of London had established that the silver used for this purpose - "finishing knife handles" - had to be of good alloy; while even earlier, i.e. in 1327, the Society of Goldsmiths of London granted letters patent complaining that "the cutlers in their workshops cover the tin with silver with such meticulousness and skill that the same cannot be distinguished and separated from the tin, and thanks to this they sell the tin thus covered as precious silver, to the great damage and deception of us and the people." [9]

In the reigns of Henry IV and Henry V various parliamentary laws were passed prohibiting the gilding of any metal other than silver, and the silvering of any article except knights' spurs or articles of noble armour. Probably the same method, passed down for many centuries, is referred to in two of the regulations in the first code of local laws promulgated in 1625 by the Sheffield Cutlers' Society. One of these prohibited the use of gold or silver on the blades, brackets or handles of knives worth less than 5 shillings per dozen; the other established that for the damasking, inlaying and studding of superior quality knives, no material of a lower quality than good alloy silver or gold should be used.

Failure to comply with these laws led to disputes and arbitrations; and in an arbitration ruling (1628) we have a clear picture of the violations caused by “counterfeit material, by which an ignorant any or other person may be induced to take the same for silver or gold”. The local law is described as “relating to the mixing of gold and brass, or of silver with tin or pewter for use or employ in the shading, damasking, gilding, silvering or other ornamentation of knife handles, brackets and blades, or of any part thereof, or in any other article of cutlery".

It is instructive to note that the defense mounted by the transgressors against these Ordinances consisted partly in the fact that they contravened one of the laws mentioned above, that of Henry V, chapter 3, (1420), and it will be seen later how (with all probability) undertaking repairs to a single knife of the species referred to in this dispute helped to reveal to Thomas Boulsover the possibilities of fusion plating – in other words, to lead to the invention of the Sheffield Plate .

The above references to the earlier use of silver and gold for plating and ornamental purposes in England naturally lead us to the question: Previously, how were these knife handles and blades plated? Certainly not through a process of short duration, or incapable of withstanding the use of items subjected to constant and daily consumption. As an answer to our question, we need to look at what is called “ close plating ,” in one form or another. This is the only system by which steel or iron, even today, in any established manner and with fully satisfactory results, can be covered with silver. Close plating has been so persistently associated, and consistently confused, with fusion plating, that it will not be out of place here to explain the former in detail.

Practically any metal susceptible to welding can also be subjected to close plating . The process is, however, laborious, and is usually applied only to smaller articles of everyday use which require a greater resistance force than ordinary hollow-ware , or the possession of a sharp edge, for example knife blades and snuffers; or pointed or pointed ends, such as forks, skewers, cheese paddles, or lobster utensils; or force, as in the case of bridle bits, spurs, harness fittings, and carriage door handles.

Although close plating , as performed in the past and today, is absolutely simple in its main aspects, only with the utmost patience can one achieve, and with constant practice maintain, expert manipulative skill. The process can be described as follows: - After having first been smoothed and perfectly cleaned, the article to be plated, to ensure complete adhesion of the substance to be deposited, is immersed in ammonium chloride, which acts as a flux, and later in molten tin. A silver foil, thinned by beating and cut to the required size, is then placed on the article and fitted as evenly and perfectly as possible. After having superimposed the silver foil on the steel in every part by pressure, a heated soldering iron is delicately passed over the entire surface. By means of this operation the tin is melted and forms a weld between the steel and the silver that covers it. The surface is then carefully smoothed along its entire extension with a heated soldering iron; carefully removed the abrasive fragments and metal particles and flattened the edges by burnishing, the surface is then ready for finishing by hand or with the aid of a sanding machine, as is usual with all articles, whether plated or silver.

This method of close plating , which we must consider as the forerunner of the equally established fusion plating process, barely survived after the latter came into common use. This is because it could not prevent the new competitor from gradually monopolizing the production process of common receptive and ornamental pottery. The method of close plating appears to have been so effectively supplanted by its more formidable rival, fusion plating, that we have to wait until the early part of the 19th century. before, after a few years of effort, it becomes appreciated again. In the 18th century At least two advanced patents for close-plating had been produced, one by Samuel Roberts, adapted for making spoons and forks from iron or "any compound or white metal ", and also for making candlesticks from the same materials. His patent sounds like a decisive attempt to resurrect close plating by testing its possibilities in those articles that required both utility and decorum on a daily basis. However, these products were not successful, being too heavy to use. They were also prone to rusting. In the year 1779, ten years before Roberts' advanced patent, another patent had been produced by a London jeweler, Richard Ellis, who significantly mentions his method as a "new way" (i.e. supposedly an improvement in close plating ) . A careful examination of his patent description leads us to the conclusion that it refers to the solder elements used during the implementation of the close plating method. Here, however, as in Roberts' case, the obscurity of the expression almost suggests that, however comprehensible the process may have been to the inventors themselves, the desire was to confuse the reader rather than to clarify what was undoubtedly the result of a lot of reasoning and careful research. Little was known of both thereafter, and throughout the period of the Sheffield Plate industry, the only means by which this older process was prevented from dying out were its adaptation to cutting blades and snuffer handles. , to the ornamentation of steel buckles, and its use by cutlers for knife blades. The durability of close plating items depends on whether they were exposed to excessive heat or humidity. The blade of a knife or fork plated by this method, if held for a moment in the flame, quickly loses its silver coating, while in a humid environment the metal of the lower layer tends to rust, and consequently the silver bubbles form.

Sir Edward Thomason (of Birmingham), in his “ Memoirs of Half a Century ,” vol. I, p.36, sheds interesting light on the subject of close plating and its revival in the early 19th century. His observations are as follows:-

In early January 1810, I enlarged the production facilities to add a new business - the steel plating of knives, forks, spoons, etc. For in this period the idea prevailed that there was no affinity between steel and silver, and that a tool must be found which combined or had an affinity for both. This instrument was tin, an object previously known but which had not been acted upon as scientifically as it should have been. I succeeded, and my manufactures in this new series were appreciated by the public, as the following letter dated 26 February 1810, Northumberland House, and signed "Percy" will prove:-

Northumberland House, 26 February 1810.

"Gentleman,

having mentioned his plated steel knives and forks, and imitation silver spoons and plates, to a gentleman about to leave for a country where there is great difficulty in procuring earthenware, he is very desirous of taking some with him. I will therefore be very obliged to you if you send me as soon as possible a dozen copies of each article, with the relevant bill, since I must hope that in the meantime you have managed to make some plates. However, should there be any shop in town to which you send your goods, it would perhaps be better to direct me to that shop, rather than have the items flown in from Birmingham, so that I might see a greater variety to choose from. I am anxious, Sir, to know whether you have lately produced any new invention, and, furthermore, whether you have been able to convert Japanese leather to any use. Should the Club you mentioned to me when I was in Birmingham publish your dissertations or lectures, I would very much like to see them.

"Rest,

“His obedient servant

“PERCY.”

“Egr. E. Thomason, Church Street, Birmingham.

I can say that the new production has occupied a large part of my free time this year, to see which classes of articles could meet my expectations; and it seemed that this method of plating was confined to small articles, and that the table-plates to which the noble Earl Percy alludes, could not be properly made.”

BOULSOVER'S DISCOVERY OF FUSION PLATING

Desolately vague and unsatisfactory are the accounts handed down to us on the way in which Thomas Boulsover 10 laid the foundations of the Old Sheffield Plate, focusing on hitherto unknown affinities between metals. Tradition has it that in 1743, while he was pursuing his craft as a cutler and was engaged in the banal repair of a knife handle, the behavior of the silver and copper used in the decoration attracted his attention. What did he see? Chroniclers provide different answers to this question. Hunter 11 , avoiding details, simply says that, since the handle of the knife was composed partly of silver and partly of copper, Boulsover was "struck" by the possibility of combining the two metals. Others, more precise, assert that this combination actually occurred before Boulsover's eyes, having been caused (1) by the melting, due to accidental overheating, of the silver and copper in the handle; or (2) by the fact that the silver thus melted adhered closely to the copper of a penny which he had accidentally inserted into the vice as a wedge. Another version rather lingers on a later event – the discovery that metals, after coming together, in combination under pressure retained their ductility separately, while behaving as a single object when manipulated. It was this, the statement goes, that surprised Boulsover when, wishing to spread the silver so as to cover an exposed spot, he put the handle of the knife "through the rollers," and found that instead of the silver expanding on its own, it the copper stretched together completely in unison. 12

That this, and not adhesion by fusion, was the vital discovery seems an irresistible conclusion. By subjecting an old copper penny and a sixpence coin to the flame of a blowtorch, anyone can easily demonstrate in a rudimentary way the role that smelting played in the production of Old Sheffield Plate . And he will find it impossible to believe that, despite the common use of soldering, it fell to Boulsover to be the first in 1743 to cause a torch to come into contact with silver and copper. It may be, however, as has been suggested, that the commercial importance of this had not "struck" anyone before him, and that it only became instructive when combined with the discovery that the joined metals were completely homogeneous and workable. Although the fortuitous presence of suitable rollers, unusual accessories for a cutler's shop, aroused suspicion, it seems possible that this was the real discovery.

It is at least very unlikely that Boulsover could have been fortunate enough to be favored by two simultaneous "accidents", one revealing the feasibility of fusion plating, the other that joined metals could be stretched indefinitely under pressure. However, lacking any explanation from Boulsover himself, and any strictly contemporary narrative, it must be admitted that these are all conjectures. Weighing the odds is of little help in solving the mystery of what really happened in Boulsover's attic. Perhaps, after all, there was some combination of intelligent seeking, good fortune, and what is, in a familiar expression, called the power of making two and two four. 13

Other activities for which he laid the foundations in subsequent years, such as the creation of rotary rolling mills, the production of saws (by means of the new rolling process), spades, shovels, etc., would, one must believe, have passed on the memory of him up to us today, as one of the greatest pioneers of the commercial industries of the 18th century.

It is said that the old saw manufacturing process involved the laborious method of obtaining the blade by beating a steel bar. Boulsover is credited with substituting for this method the simpler one of rolling, with the advantages of which his experience of silver plating had made him familiar. He also introduced the ingenious but then innovative method of adjusting the teeth of the saws so as to give “pitch” without the inconvenient main concern of keeping the cutting side of the blade thicker than the back. It was for this industry that he built workshops on the stream below his house at Whiteley Hood – beginning, as he said, with a purse that had no neck and ending with one that was only a neck. At Bowser (i.e. Boulsover) Bottom the workmen's sheds can still be seen. The remains of the mills, clearly visible not long ago, are now, however, almost entirely destroyed. However, the dam that provided hydraulic energy remains. Shortly after Boulsover's death, his daughter, Mrs. Hutton, built a small chapel for the workmen between the mills and the Hall . It still stands, used as a barn, as part of the Mason farm (see illustrations, p.3).

DESCRIPTION OF THE METHOD

The Boulsover method of fusion plating is still being performed today, and the best we can do is to recount point by point the description given by Mr. William Adcock Ellis, whose firm has been steadily engaged in this method for over a century. Mr. Ellis has also kindly provided the ingots pictured here. It should be noted that the modern procedure differs only in certain minimal details from the methods adopted in the very early years of the industry.

“About a century ago, when trade in Old Sheffield Plate was at its highest, it was discovered that the most reliable metal on which to plate, and most suitable for sheet rolling, was copper lightly alloyed with zinc and lead, a mixture discovered thanks to an experiment to produce an easily workable metal, neither too hard nor too porous, while the silver coating was lightly alloyed with copper in the same proportion as common silver (i.e. 925 parts pure silver versus 75 parts alloy).

An ingot of the above metal was taken, which varied from a thickness of 1½" to 1¾", and 2½" wide by 8" long, or larger, depending on the weight and size of the plated plate required for production, and the surface (or both surfaces during plating on both sides of the ingot) was planed to remove casting irregularities, resulting in a solid surface. Then the ingot was filed and scraped until all the imperfections on the face disappeared. The silver plate was then cut almost to the size of the face of the copper ingot, and with a thickness of the quality of the pottery required 14 ; this after having treated the plate in a similar way to the copper ingot. Then the two prepared surfaces were placed together, taking great care not to allow any dirt or moisture to remain on the surfaces; then these surfaces were pressed together with force so as to make the two faces fit together in an absolutely regular way. Today this press molding process to expel all air particles, before casting, is carried out by means of a powerful hydraulic press; previously it was carried out by a man, called a “ bedder ” 15 , who held a piece of iron weighing about 20 pounds, while a second man hit it with a heavy hammer. This flattens the two surfaces, embedding the silver into the copper.

To protect the silver from fire, a copper plate was spread over it, covered with a plaster solution to prevent it from adhering to the silver. The three pieces of metal were tied together with wire (or the five pieces in the case of double-plated metal, i.e. the one in which both sides had been silvered), then the edges where the silver and copper came into contact. The ingot was then ready for the smelting process and deposited into a furnace heated with coke fire, where it was placed, and watched with the utmost care through a small hole in the furnace door, until the silver plate of the ingot of copper did not begin to "cry" (this is the technical term), that is, it did not begin to drip down the sides of the ingot. The time had now come to remove the ingot from the furnace, and great care had to be taken when moving it. Appropriate pliers were used to firmly grasp the ingot by the sides and hold it in place during movement. Finally, the ingot, after enough time had passed for it to cool, and before sending it to the rotating mills, was carefully thoroughly cleaned by immersing it in acids and then rubbing it with sand and water.

In the event that some imperfection appeared on the plate after the lamination method, a section of the plate could be cut and eliminated, or the "French Plating" method, described on p.96, could be used as an alternative; but since the time taken up by this process weighed more than the small section of material eliminated, there was little incentive to use it.”

As to the question of whether plating on all four sides of the ingot had ever previously been undertaken, one experiment proved that by covering all four sides of an ingot with copper plates coated with silver and plaster, it could not be carried out inside a quantity of heat sufficient to bring the copper to the necessary melting temperature.

When only two faces of the ingot are plated, by exposing two sides of the copper surfaces to the furnace, the required heat is readily achieved.

TO WHICH PURPOSES WAS THE INVENTION OF MELTED POTTERY FIRST APPLIED AND HOW THE TWO PIONEERS FOLLOWED OTHER INDUSTRIAL INITIATIVES

Some extremely interesting additional information on the Old Sheffield Plate industry is given by some manuscripts left by Charles Dixon, a candlestick maker, who was born in Sheffield in 1776 and died in 1852. For some years before his death he took great care in compiling a register of events, anecdotes and trends of the times in which he lived, and as he freely associated with men then engaged in the manufacture of the Old Sheffield Plate , his recollections on this subject are of such importance as to merit reproduction in his own picturesque phraseology of the writer;-

“A person named Thomas Boulsover was the discoverer of the art of plating copper with silver. He was a cutler by profession. In the year 1743 he had a work in his hand in which the back of the knife was covered with silver soldered onto it. Realizing that he had run out of silver, he placed it all, just as it was, among the rolls at random, and found that the hard and the soft stretched together, which made him think about cause and effect.

Boulsover then began to carry out experiments. He discovered that the silver melted before the copper, and lay on the surface of the copper in a fluid state, so that when the heat had been applied long enough to melt the silver, it and the copper became a single solid body 16 , which could be laminated to any size or thickness.

The first use which Mr. Boulsover made of his discovery was in the manufacture of plated buttons, which seemed to answer his expectations very well. Since the discovery of plating was his, he kept it secret, and for a long time he had no opposition in this activity.

He cut out the buttons "on the fly" with a pallet and an awl, welded to the base, and then burnished and smoothed them. The greatest difficulty encountered was the need for money to expand their business thanks to this. He had no capital or little of it, and until then what he earned came from the result of his manual work.

Mr. Pegge, of Beauchief 17 , who knew Mr. Boulsover and his family a little, was the person to whom he decided to turn for help. Receiving him courteously, Boulsover explained the nature of his difficulties, showing him the models and providing him with details on the prospects for selling the buttons. Mr. Pegge understood the feasibility of the speculation and lent him £70, wishing him success. At the end of 12 months Mr. Boulsover visited Mr. Pegge again. Mr. Pegge says, “Well, Thomas, how are you? What, did he come to borrow more money?” “No, sir,” was the reply. “I have come to pay you the money I borrowed from you with interest.” “Really, Thomas?” "Yes, sir". “Well, Thomas, I don't want you to insult your business to pay me. I don't want money if it will be useful to you for a little longer; pay me only if you are able to save it conveniently.” “Oh, yes sir, I can spare him; and I also have a lot of money to carry on my business." “Well, Thomas, your trade must be as profitable as making money.” "Yes, sir; but it is a better business than making money, for I am able to sell my buttons comfortably for a guinea per twelve pieces, and the silver does not cost more than three shillings per twelve pieces; therefore making money costs more than it costs me.”

He paid Mr. Pegge and thanked him. He was very successful with his buttons, and by decorating them he obtained a great variety of designs. In business for some years, he sent his moldings, which he had taken great care of, to Mr. Read, refiner, at Green Lane, and in a short time he sent him back silver to the value of £100 - the workshop shapes were worth it.

The above story shows how, after some experiments, Boulsover had applied his invention to the manufacture of buttons, and to other small articles which had previously been made only of silver. It was Joseph Hancock (who will be discussed in more detail later) who understood the wider commercial possibilities of the new process, which he applied to a wider range of goods, initially manufacturing saucepans, then coffee pots, hot water jugs and candlesticks. , etc.

The late Thomas Nicholson tells an anecdote that Boulsover was treated very badly by a representative he employed in the early days of his invention. Hired to visit Boulsover's clients, this individual passed many of the orders he received to an accomplice in Sheffield, while making it clear to his employer that he was unable to conduct business on his behalf, as no one believed in the new method. Be that as it may, Boulsover devoted himself mainly to other ventures, in which he spent a substantial sum of unprofitable capital, while later wealth was built by those who had limited themselves to the production of plated pottery. After spending about fifteen years in manufacturing, Joseph Hancock abandoned the manufacturing of finished products and turned to trading rolled metal for manufacturers. We can place the date of this turning point between the years 1762-65, about the same time as Boulsover took up the manufacture of saws, etc. Originally the metals were transformed into plates by beating thanks to manual labor in the rooms where they had first been melted. They were later rolled by hand power, and about the same time that Joseph Hancock began rolling metal commercially, horsepower and water power followed. Finally, steam was used to operate the rolling mills.

The foregoing explains why, in the quotation from the old Lists given on the following pages, Boulsover and Hancock are not included in either 1774 or 1787 in the silver plate category. In the first list Boulsover appears under this heading, “Boulsover, Tho. & Co., Manufacturers of Saws, Fire Guards, Sharpened Tools, on Sycamore Street”; the only Joseph Hancock mentioned is “Hancock Joseph, Cutler, in Norfolk Street”. Boulsover is not mentioned in the 1787 Directory, in which Joseph Hancock is described as “laminator of plated metal, in Union Street.” There is reason to believe that earlier (about 1771) he had been engaged in the same industry in High Street, on or near the site later occupied by the silver-plated metal-making operations of William Hutton & Sons , now home to the Newsome, chemist, building. He established the Old Park Silver Mill, which still exists, on Club Mill Road, Hill Foot, substituting water per horsepower for plated metal by rolling.

The books of Thomas Bradbury & Sons show how Hancock laminated pottery for his predecessors in the years 1783-1787 –

|

DOCTOR. |

MR. JOSEPH HANCOCK, SHEFFIELD -AGAINST- |

CR. |

||||||

|

1783 |

At the checkout |

£ |

Shillings |

Penny |

1783 |

£ |

Sc. |

P. |

|

9 Aug |

5 |

5 |

0 |

24 June |

||||

|

13 Sept |

5 |

5 |

0 |

For balance from OL, p.244 |

176 |

15 |

4 |

|

|

1 Nov |

5 |

5 |

0 |

For lamination as above. Invoice in 1783 |

73 |

10 |

6 |

|

|

20 Dec |

5 |

5 |

0 |

1784 |

65 |

12 |

6 |

|

|

1784 |

1785 |

58 |

12 |

2½ |

||||

|

17 Feb |

5 |

5 |

0 |

1786 |

56 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

29 May |

5 |

5 |

0 |

1787 |

30 |

14 |

8½ |

|

|

21 Aug |

5 |

5 |

0 |

|||||

There are also in the same ledgers some entries relating to Boulsover, as a purchaser of goods from the same firm (M. Fenton & Co.) in the years 1778-79-80-81-82.

THE NEW INDUSTRY AND ITS POSSIBILITIES

As a result of Boulsover's discoveries, supplemented by those of Hancock, a new and important branch quickly sprang up on the already existing cutlery industry. There was naturally a brief initial or experimental stage during which, in the hands of the inventor, the new process was put to the test, since its potential needed to be motivated. Mr. Leader, in his " History of the Cutlers' Society ", does not accept the version that explains Boulsover's limitation to the silver-plated manufacture of buttons, snuffboxes and light and small articles, with the fact that he did not immediately understand the possibilities of his discovery. Leader leans towards the opinion that Boulsover wisely sought, at the outset, to demonstrate the value of the method by its practical application to the articles in which the Sheffield industry was chiefly active. And among these there were not only cutlery items, the ingenuity of which can be understood from the large number of "silver cutlery makers" who quickly used the new material; even minor manufactures which can be said to be almost indigenous to the place were ready and available, admirably adapted to experiments, and these products had a ready market. The production of buttons, for example, in the 18th century. it became important quickly enough to justify joining the Cutlers' Society in defending this trade, even though it was outside the corporation's jurisdiction. The dispute in question was in the interest of the manufacturers of uncovered buttons, and the result left them free to carry on their secondary business without inconvenience arising from the old statutes passed in the interest of the manufacturers of textile-covered buttons. This victory shortly preceded the discovery of Boulsover, which thus stood out in a booming local business. Producing not only buttons of horn, but buttons perhaps of silver and certainly of baser metals, such as brass and an amalgam known as “ alcomy ” (which was said to resemble gold), the adequacy of the new method for enlarging a existing trade would have been immediately evident in many Sheffield workshops. His adaptation did not eliminate the cheaper buttons derived from the clothing of the humble, nor did plated pottery supplant silver buttons. It did, however, provide for the needs of an intermediate class ready to pretend to have a precious metal that it did not actually possess.

It is worthy of note that the plated button, the very first article produced by Boulsover, would hold its place among the many productions made from plated molten metal with more tenacity than any other experimental article.

Courtesy of Messrs. Firmin & Sons, of London, the author is able to illustrate on the following page examples of buttons made from a molten copper plate, some of which were obtained from molds existing from the reign of Queen Anne (probably used in those days for punching silver buttons).

Messrs. Firmin are perhaps the oldest button manufacturing company in the country; their business can be traced back to 1702 and undoubtedly existed before then. The method of producing these buttons has not changed significantly in its main characteristics since the days when Boulsover manipulated them with the help of a pallet and an awl. Messrs. Firmin state that copper-plated buttons for uniforms and liveries are now made of plated molten metal to the same extent as before, and that, since the discovery of the new process, this method has been continually and systematically carried forward in their factory. Electroplated buttons are not able to withstand the heavy wear and tear of current use.

(An interesting advertisement in a Dublin newspaper, the “Faulkener's Journal” of 24 February 1747, runs thus: “John Roche, Usher's Quay, Dublin, manufactures gold, silver and plated buttons.”)

CANS

Box making was also an old Sheffield industry too profitable to be scorned, and ripe for expansion such as that brought about by the Boulsover discovery. In 1680 the Knifemakers' Society, acting as an intermediary between the producer and the consumer, established a warehouse in which it received the goods and undertook their distribution on behalf of the producers, and the transaction records show that (in addition to the cutlery) they were deposited at the Company and were sold in considerable quantities to merchants, snuffboxes and money boxes, produced by the Freemen of the Company (including one Isaac Hancock). 18 The trade appeared so profitable that when the Society of Cutlers later let itself be betrayed by a manufacturing zeal that was in itself ill-advised, it was setting up a box trade among its activities. This episode is not only interesting as such, but is linked to the history of the Old Sheffield Plate , as Thomas Law, one of the very first tacklers, played an active role in managing, sourcing the materials needed for, and perhaps even manufacturing, the cans. This speculation was, however, very short-lived, and Law eventually purchased some of the tools and utensils, while the stock he had accumulated was shipped to London to be sold. Unfortunately there is nothing to indicate whether this foray into industry underlines an eagerness on the part of the Cutlers' Society to share in the benefits of Boulsover's invention, then six or seven years old, or whether the boxes were of the type manufactured in 1860 – of iron and perhaps brass, the lids of which were engraved or “written” with drawings or lettering . 19

Among the very first objects to which the old tacklers turned their attention were snuffboxes of all sizes. Boulsover and Hancock both made these cans, usually with removable, unhinged lids. As the plating industry developed, Sheffield manufacturers concentrated their efforts on larger items, and although box making was still carried on in the city when Sketchley's list of 1774 was published, the business he gradually slipped into a branch of the Birmingham jewellers. Some small surviving specimens were obviously used as hairpiece boxes; others happen to be just big enough to hold four George III shillings.

The following two pages provide some illustrations of top quality examples, with lids and bases decorated in bas-relief. The lids not rarely show that they have been engraved by hand; others were made from finely cut steel molds. The source of origin of the boxes depicted here is uncertain; the date of manufacture dates back to approximately the years 1750-1765. The lids, manufactured separately, were joined and attached to the top surface of the boxes by overlapping the sides to secure them rigidly, and to make them more practical, a loose sheet of unplated copper is secured under the lids. The bases are fixed by the same methods, the sides hot-stamped by boiling and soldered together, the joints remaining clearly visible. The insides of the boxes are not covered with tin as was usual with Sheffield-made items, and reveal bare copper once the lids are removed. Some collectors attribute the manufacture of these boxes to the French. It may be that the covers, which often depict classical subjects, were imported from Sheffield manufacturers and therefore finished. However, since these boxes sometimes bear typical English characters and lettering in English, they are most likely of local production, although at first glance they appear however unforeseen. Furthermore, being normally made with removable lids, they are likely to be among the earliest examples of the Sheffield cast ware industry.

BUCKLES

It is impossible to share the opinion of many writers on the Old Sheffield Plate that, among the articles in the production of which the pioneers of fusion plating were interested, shoe buckles had their place. Part-plated buckles had been known since about 1659, when they became fashionable. Specimens can be found today in some collections, but their method of plating is too obscure to justify any confident statement as to its precise nature. It is evident, however, that the worker capable of making and decorating knife handles with silver could just as easily treat buckles in a similar manner. And when we turn to examples of buckles from the Boulsover period, we find them made for the most part by close plating 20 , although there are others of solid silver, steel or common iron, gilded brass, gold-like and other cheap varieties of combined metals . Cast-plated buckles, however, are conspicuous by their absence, explained by the fact that their manufacture presented three difficulties. First, the copper base would have been too soft and bendable to withstand rough use; second, to obtain the necessary thickness on the bridge and the taper towards the ends, endless and careful hammering would have been necessary; and third, the cutting process would have exposed large unworked sections of bare copper to the inherent difficulties of handling, for the purposes of plating the sides. And beyond this, it should also be remembered that the tin soldering of many delicate decorations on such small items could not be done in such a way as to ensure adequate durability. Very rarely do we come across gold-plated buckles with a copper base, but their manufacture, involving extremely delicate treatment, must have been expensive. Mr. S. Mitchell, giving in 1840 a list of articles made by Thomas Boulsover, makes no reference to the plated buckles so often attributed by others to their ancestor.

PART II

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE VERY EARLY SHEFFIELD PLATE MAKERS

THOMAS BOULSOVER

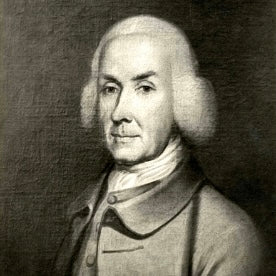

Boulsover was born in the year 1704, and died at Whiteley Hood Hall, in September, 1788 (being interred in St. Paul's Church, Sheffield, on 12 September). He was generous and free from distrust to a degree that perhaps allowed others to obtain from his invention the fortune that was rightfully theirs. By kind permission of the great-grandson of this eminent man, Mr. J. B. Mitchell-Withers of Beauchief, near Sheffield, the author is able to reproduce a portrait of his ancestor. An Old Sheffield plated tray given by Boulsover to his daughter, Mr. Mitchell-Withers' great-great-grandmother, on the occasion of her marriage to Joseph Mitchell in 1760, is illustrated below.

JOSEPH HANCOCK

The widespread occurrence of the Hancock surname in Sheffield, and the fact that there were numerous contemporary Joseph Hancocks during the 18th century, make the identification of their numerous personalities difficult. The result of careful research forces us to recognize that while our knowledge of the silver plater Joseph Hancock is uncomfortably thin, the scant accounts usually accepted about him are also not free from strong doubts. Eyam claims that he was descended from a family whose fate constitutes one of the most heartbreaking tragedies of the Plague in that village in 1666. The tradition may contain some elements of truth, although the Church Records of Eyam have been searched in vain for evidence, nor is it It is possible to find in the records of the Society of Cutlers any confirmation of the statement that his ancestor was apprenticed to a person in Alsop-Fields, near Sheffield; except that he was an Isaac Hancock mentioned in 1680 as a distributor of snuffboxes intended for sale to the Cutlers' Society. On that date a mark was awarded to this Isaac, proof that he had passed the qualifying apprenticeship and obtained the Freedom, but since the documents of his apprentice contract and his admission have not been found, there are no indications of his parentage . Even the oft-repeated assertion that Joseph Hancock served as an apprentice to Thomas Boulsover himself does not stand the test of fact. He was born in or about 1711, so under normal conditions he would have been indentured in 1725, and would have been entitled to the Freedom on coming of age in 1732. The list of apprenticeships of that period contains two entries: (1) Joseph , son of Benjamin Hancock, apprenticed in 1728 for 3¾ years to Thomas Mitchell, cutler; (2) Joseph, son of Simon Hancock, of Barlow, nailmaker, deceased, apprenticed in 1732, for 1 year 8 months, to John Green, cutler, admitted to the Liberty in 1734. Of these the former answers best to the criteria of our research. It is assumed that the apprentice, having been, as was usual at that time, taught by his father, was sent to complete his training under another master. Although no admission to Liberty is recorded, his time as a pupil would have ended in 1732, the year Joseph Hancock, the future silver plater, came of age. And given Boulsover's connection to the Mitchell family, the apprenticeship to Thomas Mitchell is not without significance, as it suggests that some confusion could easily arise over time between this name and that of Boulsover as Hancock's master. This would be especially possible if, as is likely, Boulsover and his relative, Mitchell, worked in the same buildings. In fact, we note that in 1774 the Assessor's Office established its residence in a "dwelling recently occupied by Mr. Thomas Boulsover, located at the head of a court in Norfolk Street", owned by Mr. Joseph Mitchell 21 . It may also be noted that Boulsover himself did not gain Freedom until 1726, if this entry refers to him: “Thomas, son of Samuel Boulsover, apprenticed to Joseph Fletcher, cutler, Freedom in 1726.” It must be admitted, however, that although this Samuel is a native of, and apprenticed to, the Parish of Ecclesfield, no record of the birth of Thomas Boulsover has been found in that register.

Such speculations would be useless if an oft-made assertion could be proved that Joseph Hancock was a brasssmith by trade, for in that case he would have been ineligible as a member of the Cutlers' Society. This thesis can immediately be rejected, because there is no shadow of a doubt that the Joseph Hancock with whom we are dealing was the Joseph Hancock Master Cutler in 1763-4. This is proven by irrefutable evidence. In a description of Sheffield, published in 1764 in the " Gentleman's Magazine ," the Rev. Edward Goodwin, a careful and well-informed authority on all things concerning the city, speaks of this Joseph Hancock as the "present Master Cutler." Newspaper announcements of his death in 1791 repeat the assertion; and Mr. Hunter 22 , who wrote while the memory of Hancock was still alive, and who probably knew his widow, who died only in 1802, had no hesitation in speaking of Hancock as a member of the Cutlers' Guild, "father of the silver-plated manufacture”, and Master Cutler in 1763. Appointed Assistant in 1757, this Master Cutler successively held the positions that led him to the presidency, and then served, as was custom, for another twelve months as Researcher, leaving the office in August 1765. In the same year that he was Master Cutler, Joseph Hancock was elected Trustee of the city. He was one of the thirty original Keepers of the Assay Office appointed under the Act of 1773, and continued to hold both positions until his death on 25 November 1791, aged 80.

The year 1761, in some records, has been given as the date Joseph Hancock began manufacturing plated wares. It will be seen later that Charles Dixon, mentioned above, places it in 1751.

In his historical introduction to the 1797 Directory, Rev. Edward Goodwin gives the date “about 1758.” He says (p.21):-

Silver-plated brass and copper buttons were made by Mr. Thomas Boulsover about 50 years ago. But about 1758 a manufacture of this composition was begun by Mr. Joseph Hancock, an ingenious mechanician, on a more extensive scale, comprising a great variety of articles, such as tea-pots, coffee-pots, beer-steins, cups, candle-sticks, &c. etc. Since then this branch has been continued by various companies with great profit, which has greatly contributed to the wealth and population of the city."

And from the same pen we have, in the communication to the above-mentioned “ Gentleman's Magazine ” (1764), a further indication of Hancock's various activities. After speaking of the silver-plated manufactures, Goodwin states: “There is similar reason to believe that snuffboxes, candlesticks, etc., were first made here, of a quality of coal called kennel , or long-flame bituminous coal (formerly obtained near this locality), by Mr. Joseph Hancock, the present Master Cutler”. The memory of these bituminous coal articles 23 has been lost, but an earlier reference is found in the account of a visit made to Sheffield by the Countess of Oxford in 1745, when her lordship "was generous enough to make gifts" to her retinue. of carbon articles”. For our present purpose this is important, as it emphasizes what was said later about the ease with which Sheffield craftsmen substituted newly invented pottery for the materials usually used in the manufacture of many articles.

Reviewing earlier references to the plating industry one cannot help but be struck by the extent to which, in the eyes of his contemporaries and immediate successors, Hancock eclipsed the fame rightfully belonging to Boulsover. It is clear that in local consideration the former more than the latter was, to use a term often applied to him, "the Father" of manufacturing. We have noted above a persistent determination to regard Boulsover's discovery as accidental, and to belittle the use to which he made it; this trend increased as Boulsover's efforts took other directions and Hancock showed greater resourcefulness. A newspaper article on Hancock's death (1791) reads: “This gentleman might well have been called “The Founder of the Plated Trade” in Sheffield, as he was the first person who commenced a manufacture of such articles.” And when the widow died in 1802, the statement was repeated in similar terms. In “ Peak Scenery ,” published in 1818, Ebenezer Rhodes, Master Cutler in 1808, and probable direct acquaintance of both Boulsover and Hancock (he was 26 when Boulsover died) took it further, completely ignoring Boulsover. Speaking of the Hancocks of Eyam (part I, p.42), he wrote:-

About the year 1750 a certain Mr. Joseph Hancock, a descendant of this family, discovered, or rather recovered, the art of covering copper ingots with plated silver, subsequently flattening them under rollers, and working them into an assortment of articles imitation silver plated work. He introduced this business to the city of Sheffield, where it has since become one of the most important and lucrative enterprises. Birmingham has attempted to challenge this elegant manufacture, but, with the exception of the Soho factory, it cannot expect much.”

The first impression one gets from reading this is that by "recovered" Rhodes meant that the art of fusion plating, of which he was unaware that Boulsover had been the discoverer, had already existed and been lost. From what follows, however, it is clear that the writer did not realize the essential differences in manufacturing processes. Silver plating meant to him silver plating and nothing else, and he was not interested in manufacturing methods. In fact he goes on to explain:-

“I have not hesitated to use the term “reclaimed” as applicable to the art of which Mr. Joseph Hancock has been considered the founder, for I am well aware that the practice of covering one metal with another more precious one is very ancient. That silver-plated articles, especially candlesticks, were in use during the reign of Henry VII, admits of almost no controversy. A specimen of the workmanship of that period was recently recovered from the monument to Lady Idonea Percy in Beverley Cathedral; a circumstance sufficient in itself to prove the correctness of the opinion expressed here. A few years ago, when there were fewer restrictions upon commercial pursuits, nearly 50,000 of the inhabitants of the city of Sheffield derived employment and support from a manufacture recently introduced by a branch of the unfortunate family whose rapid and almost total extinction is sadly commemorated by the gravestones. of Riley."

The darkness that surrounds Joseph Hancock's ancestors also surrounds his descendants. A certain William Hancock, previously registered as a blacksmith at the London Goldsmiths' Hall, testified before a committee of the House of Commons in 1773, complaining about the treatment of his wares by the London Tasters 24 . And White's Sheffield Directory for 1833 (p.44 note), incorrectly stating that “the first producers of Britannia metal were Messrs. Ebenezer Hancock and Richard Jessop,” he adds, “The former was the son of the aforementioned Joseph Hancock, the famous silver plater.” However, except that in 1793 there was a snuffbox maker named William Hancock, the William Hancock of 1773, and the later Ebenezer Hancock, have similarly eluded further research.

Having provided Dixon's views on the discovery of the fusion plating process and its subsequent adaptation by Boulsover, it is interesting to learn what he has to tell us about Joseph Hancock and the uses to which he put Boulsover's invention.

“Mr. Joseph Hancock, in 1751, being a man of a small capital, and a man of genius and enterprising mind, was the first to make any practical improvement in the use of silver-plated metal. It was he who went from a button to the candlestick, to the tray, to the ornamental centerpiece, to the splendid cup, etc. Thus one can see how one of the most popular professions of the city and the kingdom originated from humble beginnings, and the gradual progress achieved in the activity is astonishing.

The first items manufactured by Hancock were internally plated casseroles 25 . Among the items manufactured were plated vegetable spoons and forks, joined in two parts and filled with tin solder. Manufacturers then made salt shakers that generally contained blue glass to hold the salt. Some candlesticks were then made, and one, the Corinthian, was in excellent taste: in its construction, attention was paid to preserving the Order. The manufacturers used to mold and join the beak of the candlestick holding the candle in two parts, not knowing at that time how to plate the metal on both sides, and they called the two parts cow and calf. They also used to join any article or part of an article for double-plated metal in the same way.

A few years after plating was discovered, the art of double-sided plating, or double-plating metal, was discovered. This created a wide space for the exhibition of genius. Then the platers started the production of plates and lids, tureens, bread baskets, butter gravy boats, teapots, sugar bowls, cream jugs, etc. etc., and when the art of plated metal wire for drawing 26 was perfected, new ideas arose and the production of supports for cruets and liqueur jars, toast holders, snuffers, candlesticks, etc. began. etc.

While it grew in the plated articles sector, the trade also expanded into the silver sector and was the catalyst for great progress in this field. The silversmiths faced a considerable inconvenience, as they were obliged to send the artefacts to London, York, Newcastle or Chester to be tasted, there being at that time no tasting office in Sheffield. Transporting the goods there and then back to Sheffield was accompanied by considerable delays and expense. It was only in 1773 that a parliamentary law was passed for the Sheffield Assay Office, which was then subjected to heavy restrictions. Manufacturers were not permitted to use the same quantity or alloy to the Sheffield standard as was permitted in any other Assay Office in the kingdom: the Sheffield alloy was equal to 3 ounces and 5 penceweights of copper per 50 ounces of silver (valuable), so that at that time if by mistake or other reason any article had not been approved by the Sheffield Assay Office, it could have been approved at any other office. In 1775 there were 3,070 pounds of manufactured goods tasted in Sheffield, which proves the increase in trade in silverware, and the trade in plated wares grew in a greater proportion.

Growing further, the trade encouraged both the employer and the employee, and in the many manufactories then established, the study of patterns and fashions rapidly increased, and the ornamental making of molds was greatly encouraged.

The trade owed somewhat to Wegwood and other fine porcelain makers for many of the finest designs. The study of ancient ornamental designs constituted another source of models. While in London I learned of a person who purposely went to Westminster Abbey to discover something that might attract the attention of customers, if used in the making of teapots, vases, ice buckets, etc.

When Hancock had been in business for some time, he quickly realized how wide the possibilities for speculation were in the employment of capital. Numerous companies started trading, made up mainly of respectable, upright and persevering men. Messrs. Winter & Parsons, Tudor & Leader, Ashfort, Ellis & Co., Matthew Fenton & Co., Messrs. Roberts, Young, Mortons, etc. etc., were part of what we can call the old school; however it is to these people that we owe professional training in the trade from its infancy. There was great competition between them as to which company could produce the best and cheapest items.

When the trade was in its infancy, workers of the rank of foremen or directors were obtained from the blacksmith shops of London, and large numbers of brasssmiths were employed to emboss and hammer the parts of some articles. All the parts of the candlesticks were made from the molds under the press hammer, then joined to form the pedestal or stem, and were invariably subjected to strong brazing (or soldered in silver). This constituted a considerable expense: if on the one hand it took more time to carry out the work, on the other hand leaving the articles in a soft or more malleable state compared to today when they are soldered with tin makes them much more convenient for the buyer, and more resistant. Another source to which the masters in search of workers resorted were those men skilled in the production of cutlery or in any other activity, of which they had come to know, and who if possible they hired; from here there were some of the best laborers in the city, and at the same time good workers were considered very valuable. There have been instances of men owing their masters £100 at one time, and I will give one example.

Henry Sephton, who resided in Cross Burgess Street, and worked for Roberts the Elder (there being a Roberts the Younger at that time – the present Mr. Samuel Roberts), kept a hound horse, called “Fido”. He went to the warehouse and said to Roberts, “Well, Sir, I have looked into my account and found that I owe you £95; be good enough to get me the other £5 and make £100 debt. I will then start working with great zeal and soon I will be able to repay the amount." Roberts lent him the money to encourage him to perform his work and receive compensation. The silver platers have generally been a very respectable body of men, and I have rarely heard of any bad behavior from any of the trade. Their earnings all at once were considerable, averaging from 30 to 45 shillings a week, and some excellent workmen earned much more. At that time the masters were in the habit of keeping large stocks of goods on hand, by way of speculation, which was a great disadvantage to them, and owing to the vagaries of changing fashions the goods were often sold at a lower price. Thus they lost some of what would have been the profit, but it still kept the men busy.

Dixon's statement on the demand for work and the recruitment of brasssmiths in the new industry finds significant confirmation in the following advertisement, which appeared in Ward's " Sheffield Public Advertiser ", 26 June 1764:- "Two or three good men wanted brasssmiths to work in plating. Anyone who wishes to serve in this branch can find an excellent boost by applying to the printer of this newspaper.” Around 1772, the Cutlers' Society complained that "numerous members had abandoned the business of cutlers to become manufacturers of silver and plated articles, and yet such Freemen continued to apprentice at Cutlers' Hall, and the indenture clarified that such apprentices so appointed would be instructed in the work, trade or occupation of cutler; nevertheless, the apprentices were essentially employed in the silver and silver plate trade, and not at all in the cutlery trade, and they never learned the trade adequately.” The Company consequently warned that such conditions deprived the poorly educated apprentices of the right to freedom as cutlers, and that they could be refused admission once their contracts expired. 27

Some of the industry's earliest examples in the form of household articles are illustrated here. Pay attention to the illustration of the Tureen on p.32, since it is the very first authentic article that can be attributed with certainty to Joseph Hancock.

THOMAS LAW

In addition to what has been written about Boulsover and Hancock, the following details about other makers in the early days of the Old Sheffield Plate trade are of interest. The majority of these, like Boulsover and Hancock, were originally cutlers. Thomas Law, already mentioned in connection with snuffboxes (p.19), was born in 1719, entered the books of the Society of Cutlers as an apprentice in 1730, obtained his Freedom in 1738, and became a Master Cutler in 1753. He died in 1775. His successors in the business registered a trade mark, the squat vase [trademark], in 1784 (8 September), at the Sheffield Assay Office.

A few years after the death in 1819 of John Law, son of the first Thomas Law, the family's long connection with the industries of Sheffield came to an end, although the name was retained until 1828 in the law firm of Atkin & Oxley, "successors of the late John Law & Sons.” Through various changes of company, and type of business, the original firm is today – somewhat indirectly, represented by the Atkin Brothers of Truro Works, Sheffield.

HENRY TUDOR AND THOMAS LEADER

The very first factory of which a connection with industry can be traced was that established by Tudor and Leader. Thomas Leader, a member of an ancient family settled in the north-west, in Essex, having served as an apprentice to a London blacksmith, came to Sheffield and began trading in partnership with Henry Tudor, descendant of a family of tanners in Welshpool , in Montgomeryshire. The initial capital was provided mainly by a Dr. Sherburn, who understood how important it was to secure the co-operation of a capable London blacksmith in the development of the industry. The success of Dr. Sherburn's wise policy soon became apparent. Exceptional in their nature as blacksmiths pure and simple amidst competitors whose skill was evident in adapting the knowledge acquired in the cutlers' workshops to other metals, Tudor and Leader took first place as the largest and most notable producers of Old Sheffield Plate . It is not known what Tudor's apprenticeship was, but from his prominence in the firm and the business, it is clear that he possessed special qualifications justifying the choice of Dr. Sherburn. He came to Sheffield at a very young age, having married a sister, or perhaps a niece, of Boulsover's wife at just 20 years of age, and three years later the business was already well established.

Henry Tudor was one of the seven Sheffield smiths who, before the establishment of our Assay Office, registered his hallmark and sent silverware to be tested at the Goldsmiths' Hall in London. He was later custodian of the Assumption Office in Sheffield.

In 1761 the company received further help from Daniel Leader (Thomas' younger brother, also a native of Essex), and the fact that he was apprenticed to a box maker indicates the importance still attached to that branch of the business. trade. Many of the characteristic designs of the firm's products were, according to a living tradition among the old smiths, attributable to the artistic ability of Harry Hirst, Tudor's nephew. We have not yet come across examples of fine pottery by Tudor & Leader, made around the years 1760-65. Initials [initials] can occasionally be found on the spouts of candlesticks and there are other items bearing the mark [trademark]. In 1783 Samuel Nicholson was taken as a partner, and the name of the firm changed to Tudor, Leader & Nicholson. In 1784 they registered a pottery mark [trademark].